Organ Donation: My First Exploration of Behavioural Economics

- deciphertheday

- Dec 19, 2020

- 2 min read

Behavioural economics is becoming an increasingly discussed topic in the 21st century. It questions and refutes traditional economic principles, such as Homo Economicus; the human model of rational behaviour adopted by neoclassical economics who a) is always acting in self-interest, b) is maximising their own satisfaction, c) has perfect information (a.k.a all information about alternatives when making a decision). These are just a few of the frankly absurd assumptions behind traditional economics.

However, the world is now delving into the interdisciplinary nature of behavioural economics, involving psychology principles to form more accurate depictions of human beings as economic parties. It recognises the many limitations of the theory of rational consumer behaviour, such as the idea that humans cannot compute and analyse information instantly, we don’t always have perfect self-control (our rationality is said to be bounded), and we don’t always maximise only our own benefit etc. Nudge theory and choice architecture are two up and coming experimental streams of behavioural economics that rely on more realistic assumptions. In this post, I will be specifically looking at the role that choice architecture has played in encouraging more organ donors.

Choice architecture is simply the way, or the context in which, choices are presented or designed which influences the decision-making process. A basic example of this is if supermarkets chose to place healthier food options at eye-level, whereas junk food was placed in hard to reach locations. The types of choice architecture are: default choices (a choice that is made when one doesn’t do anything), restricted choices (choices limited by external parties), and mandates choices (a choice that you are legally required to make). These are types of ‘nudges’ in choice architecture which work to influence consumer choices for socially desirable results.

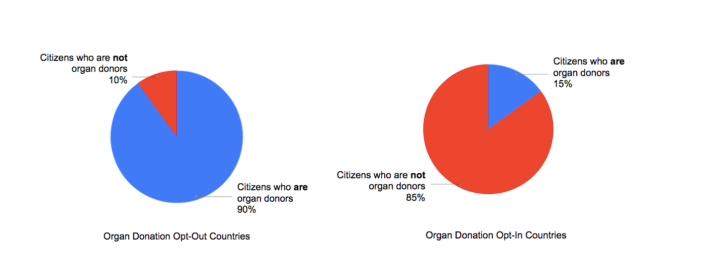

Organ donation is a problem across the world: there aren’t enough people willing to donate their organs once they die, resulting in a major organ shortage. This has caused long waiting lists for transplants and unfortunately several deaths in the waiting process. This is because many countries have adopted a default option (the option that you are automatically signed up for if you take no action) as being a non-donor. The graphs below show that when you make the choice ‘opt-out’, the default choice is to be a donor, so very few people actually make the effort to opt-out of being an organ donor.

The opt-out system has already been adopted in 25 countries in Europe, including Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal and the UK - where organ donations rates are sometimes as high as 90%. In the US on the other hand, the opt-in system has led to a great problem of organ shortages.

This insight into an area of behavioural economics sparked my interest in the subject, as I truly believe that the classical depiction of economics fails to consider several factors. As seen in this example of organ donation, the status-quo bias can play a huge role in influencing the choices made by citizens.

Sources

https://creativescience.co/status-quo-default-organ-donation/

Tragakes 2020, Third Edition Economics for the IB Diploma, Cambridge Uni. Press

Comments